At Thinkst Canary, we make the world’s easiest to deploy and manage honeypots. The high-level architecture for each customer is a web-based management dashboard (called the Console), plus the honeypots that the customer has deployed into their networks. We run the dashboard, customers run the honeypots. Our Console fleet is thousands of machines at this time, and this blogpost describes how we recently upgraded our fleet without any customer-noticeable downtime.

Background: Canary Consoles

Customers manage their honeypots, configure alerting, and review incidents, within their Console using a web browser. The Console is a key piece of the offering; it removes the pain that customers typically experience with managing fleets of honeypots. Instead of fiddling with config files and service monitoring, customers choose a honeypot profile from a dropdown on a web page, click “Deploy”, and two minutes later the honeypot has been reconfigured and the customer can carry on with their day.

Each Console is a per-customer tenant running on an isolated instance in AWS; we trade away the security risk in co-locating customer data for our increased operational pain (and are very happy with the trade, an upcoming blog will dive into this). Each Console runs its own database, and has several services (e.g. the web backend, the device communication service, and the Canarytokens service). We run thousands of Consoles, all as instances inside various AWS regions. Each instance also has Elastic IPs. However the requirements of each instance are tiny; Canaries are not noisy, the databases are in the order of megabytes, and the web interfaces don’t deal in high traffic numbers. We rely on SaltStack to manage configurations across the fleet (“highstate” ftw!)

Our decision to go with an instance per-customer (instead of, say containers, or Lambdas, or other designs) stems from two desires: keep customer services and data isolated from one another, and limit any common control fabric as much as possible (e.g. a Kubernetes control plane). Our security boundary between customer data is cleanly the AWS hypervisor, not a bunch of database RBAC statements, or Kubernetes ACLs. (Elsewhere we make heavy use of containers, Lambdas, CloudFront Functions and more, but for the core, we like the AWS hypervisor boundary.) There are additional benefits to full instances which we enjoy that we can’t easily get with other compute models, primarily regarding network traffic (e.g. multiple IPs, and true source IPs of requests).

When we started with Canary in 2014, our Consoles ran Ubuntu 14.04 (Trusty Tahr). This was an LTS release, whose standard support ended in 2019. “Standard support” means free support, i.e. no access to a support desk but Ubuntu releases security patches for public issues. This was sufficient for us.

The 2019 upgrade

In 2018, Ubuntu 18.04 (Bionic Beaver) was released. With Trusty’s standard support ending in mid-2019, we embarked on an upgrade project in early 2019 to migrate the Console fleet to Bionic Beaver. This was our first major upgrade (to be sure, we apply minor patches as they are released, the major upgrade here is to step to the next release, akin to upgrading from Windows 10 to Windows 11). The process we followed was straightforward1. For each of the Consoles:

- Leave the old Trusty Console running, serving traffic

- Launch a new Bionic Console for the customer

- Shut down all services on the old Trusty Console (database, web services, device service)

- Copy customer data from the old Trusty Console to a staging point via SSH

- Copy customer data from the staging point to the new Bionic Console via SSH

- Disassociate the Elastic IPs from the old Trusty Console, and associate them with the new Bionic Console

- Start all services on the new Bionic Console

- Shut down the old Trusty Console

This straightforward approach was effective2, and we migrated the fleet of hundreds of machines in about a week. We hit a few snags, due to how long the migration took for each customer. The main issue was the time interval between when services were shut down on the old Console, and started the new Console. That interval was the heart of the migration; data and IPs were moved, and could take in the order of several minutes (up to 15 minutes, if memory serves correctly). Customers were potentially affected in several ways:

- Anyone trying to access their Console’s web interface would have been unable to connect. Since the outage was at least several minutes long, a browser refresh would not have solved this and they’d experience frustration. We received support requests due to this.

- We have logic to detect when Canaries are offline, based on when their last heartbeat messages were received. This logic was flawed, and triggered due to the Console being down (rather than Canaries not sending heartbeats). We fixed this issue early in the migration, but it did affect some customers in 2019 as they received spurious Device Offline notifications.

- While our honeypots are tolerant of their Console not being reachable (since the honeypots will simply queue alerts for re-sending if the Console is unreachable), Canarytokens are much less tolerant of unreachable Consoles. Some Canarytokens will only give defenders a single attempt, and if the Console isn’t ready to catch the event then it’s lost.

Over the last few years, we’ve been happy Bionic Beaver users. However, all good things must come to an end and in June 2023, Bionic reached its end of standard support. Jammy Jellyfish (22.04) had been released in 2022, and was the next version we wanted to upgrade to.

Side-quest of sadness: Ubuntu Pro

When standard support for 18.04 ended last year, we wanted to upgrade to Jammy but for various reasons we weren’t in a position to execute the upgrade. Canonical (the makers of Ubuntu) provides commercial support in the form of Ubuntu Pro, where they continue to maintain security updates and patches for the older release. This feature is called Expanded Security Maintenance (ESM), and was perfect for us. Our main concern was falling behind on security patches, we didn’t care about new features. ESM would guarantee that security issues in 18.04 were patched. We didn’t need to drop other priorities to rush the upgrade, and since we’d been using Ubuntu for a while, paying Canonical for services seemed like a fair trade.

After exploring our options, we decided to subscribe to Ubuntu Pro through AWS EC2’s marketplace. There, you can spin up an instance which comes pre-built with Ubuntu Pro access or add an already-running instance to the subscription, and pay via your regular AWS bill. We had all the features of Ubuntu Pro as if we’d bought directly from Canonical, with single billing. This suited us well, at the cost of increasing our AWS EC2 instance bill by about 25%. After rolling out Ubuntu Pro across our fleet3, we were safely ensconced in the protective embrace of Canonical’s security patches and could ignore the future pain of upgrades for a little while longer. Or so we thought.

Earlier this year we underwent a regular security assessment by the good folks over at Doyensec. They identified a public security advisory for a package we used on our Consoles, osslsigncode. The issue has a CVSS score of 7.8 (High)4. How could that be? We were paying for Ubuntu Pro through our AWS subscription, we should have been getting all security fixes. Although the package wasn’t in the main repo (it was in universe), this shouldn’t matter. Canonical’s Ubuntu Pro page had the following to say about security patching in Ubuntu Pro: they’d patch critical, high and selected medium CVEs for 2,300 packages in the Ubuntu Main repo, plus an additional 23,000+ packages in the Ubuntu Universe repository. The vulnerable package qualified for a fix under those guidelines.

We figured because the package was in universe, maybe we just needed to nudge Canonical, and so reached out to them. After exchanging a handful of mails with Canonical, they confirmed that the package was at the vulnerable version, and suggested that we raise a support ticket.

But… Because we purchased our subscription through AWS, (instead of directly from Canonical) we couldn’t raise a support ticket with Canonical. We then contacted AWS support, since the subscription was paid to them.

But… They were unable to assist and advised us to contact Canonical.

This left us thoroughly unsatisfied (and vulnerable), and so accelerated our push to get off Ubuntu Pro5. We decided to upgrade the fleet to Ubuntu 22.04, Jammy Jellyfish6.

The current upgrade

In choosing Jammy, we deliberately decided against picking the very latest LTS release (24.04), Noble Numbat. Noble was just getting released and we didn’t want to pick a base that was so fresh. Jammy is two years old at this time and stable.

We already knew how to perform the straightforward upgrade (run two Consoles in parallel, shut down services on the old one, copy across data, migrate the IPs, and start the services on the new Console). However we wanted to dramatically shorten the downtime for any individual customer to the point that it wasn’t noticeable. The key here was careful ordering of operations, and replication.

In the first upgrade, the major reason for downtime was moving data between the old and new instance. The data was copied through a coordination machine, not directly between the instances. There were also several data sources that needed to be copied. For the current upgrade, we wanted to rethink this. Instead of pausing everything to move data, Dev had the idea to instead set up database replication to shift the data while the old Console was still providing services, then when the data had been replicated, cut across to the new Console. Denver set about experimenting with replication, and came up with an approach which worked beautifully7. For each Console:

- Leave the old Bionic Console running, serving traffic.

- Launch a new Jammy Console for the customer with running services, but serving no actual traffic.

- Setup database replication directly between the Bionic and Jammy Consoles, with the Jammy Console as the replica, with writes enabled.

- Shut down non-essential services on the old Bionic Console (but still continue to answer essential requests, such as Canarytokens triggers).

- For files that needed to be moved, copy directly from the Bionic to the Jammy Console.

- When both the replication and file copies had completed, shutdown all services on the old Bionic Console. This was the start of the experienced downtime period for customers.

- Perform an rsync of the files copied in Step 5, to ensure no small changes were lost if they’d changed in the intervening seconds or minutes.

- Stop the database replication, and switch the new Jammy database to master mode.

- Disassociate the Elastic IPs from the old Bionic Console, and associate them with the new Jammy Console. This was the end of the experienced downtime for customers.

- Shut down the old Bionic Console.

This recipe meant that actual downtime was dominated by waiting for AWS’s APIs to move the Elastic IPs, which took in the order of tens of seconds. Over a period of three weeks we’ve been migrating our Consoles, and it’s finally all done.

The main success criteria for this migration was to limit downtime for customers8. In that regard, the mean downtime was 25 seconds, the 90th percentile was 29 seconds, and the 99th percentile was 49 seconds. This was a great success; the limiting factor was the delay in AWS API calls to shift EIPs around, which we don’t have control over. The frequency distribution below for downtime shows two primary peaks; these are due to our use of multiple AWS regions. It shows how the vast majority of Consoles were offline for less than 30s.

The boxplot below shows the downtimes across the various regions. The migration process was managed from eu-west-1. ap-southeast-2 was the outlier with moves there taking almost 50s; however it’s home to a small number of our Consoles.

So long, Ubuntu Pro

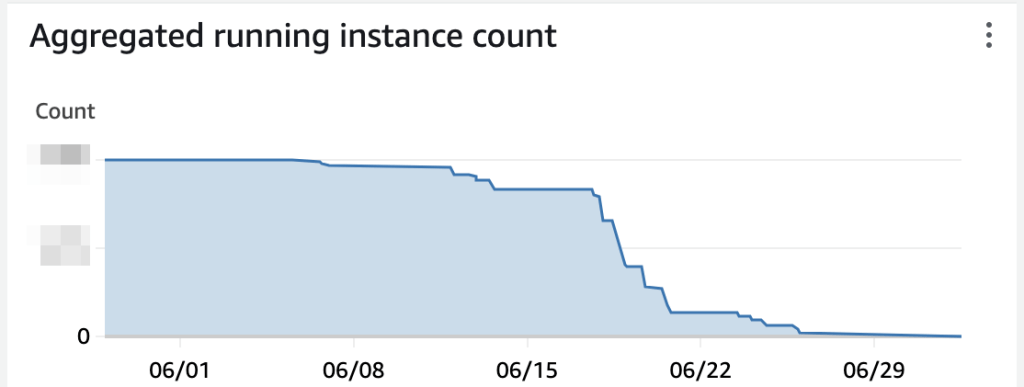

With the migration complete, our current Ubuntu Pro usage has dropped to essentially zero. The graph below shows our running Ubuntu Pro instances through June:

As a nice side-benefit of the upgrade, our AWS bills are shrinking this month.

Wrapping up

Upgrades are a necessary pain with our architecture choice, kinda like dentist appointments and long haul flights. Unlike flights and the dentist though, there’s not even a little fun to be found in upgrades. Back in 2019, we optimised our upgrade process to reduce our total effort spent on the upgrade. This time around, we optimised to reduce the downtime any one customer would experience. We shifted our fleet of thousands of Ubuntu instances from 18.04 to 22.04 over a period of three weeks, with a mean per-customer downtime of 25 seconds.

This migration gives us a base for the next three years. Based on our experience with Ubuntu Pro, we’ll migrate to 26.04 in 2027, before standard support ends for 22.04.

Footnotes

- These steps ignore less important details like updating Salt keys and monitoring configurations. ↩︎

- A discarded option was the idea of in-place upgrades, or in Ubuntu terms, do-release-upgrade. This approach requires every package to be individually upgraded and is both longer and less reliable. It simply wasn’t feasible. ↩︎

- AWS reached out last year about our usage as a potential use-case to be referenced in a re:Invent talk, which suggests our deployment was unusual in some manner. ↩︎

- The vulnerable package has no public exploit, and was only accessible to authenticated users of that particular Console, who are all commercial customers. We found no evidence of exploitation. Due to the aforementioned architecture choices, even in the event a customer had exploited the issue, they would only get access to their own data. It’s exactly this sort of situation that justifies the extra operational pain in maintaining instances per-customer. ↩︎

- We considered vendorizing the package into our internal repo, but it stuck a bit in the craw that after a year of license fees without any demands of Canonical, we couldn’t get one actually vulnerable package updated. ↩︎

- This upgrade was also paired with a significant upgrade of SaltStack across our fleet, but that’s less interesting except we upgraded things slowly to avoid smooshing a bunch of changes together. ↩︎

- These steps ignore fiddling with security groups, monitoring, SaltStack and more. It’s the rough outline. ↩︎

- Apart from, you know, actually migrating the darn things. ↩︎